Sonya Remington Doucette, Bellevue College

Heather U. Price, North Seattle College

Deb L. Morrison, University of Washington

Irene Shaver, Washington State Board of Community and Technical College

Abstract

This article provides a rationale and resources for teaching climate justice and civic engagement across the STEM curriculum in

K-12 and higher education. It presents a culturally responsive approach to STEM teaching and learning that centers social justice issues arising from climate impacts, and energy extraction and development activities, with a focus on participatory and equitable solutions and actions. This approach promotes STEM curricula that introduce social justice issues into the classroom as an entry point for investigating the issues using STEM. A social justice approach allows students to make meaning of abstract and disparate STEM knowledge and skills through real-world issues aligned with their interests, experiences, identities, and communities. In this article, we provide resources for teaching STEM through climate justice and civic engagement that are being collectively developed by groups in Washington (WA) State, led by Deb Morrison at the University of Washington (K-12); Sonya Remington Doucette and Heather Price at local community colleges (Bellevue College and North Seattle College); and Irene Shaver at the WA State Board of Community and Technical Colleges.

What is Climate Justice?

A good working definition of climate justice is rooted in the histories of the people who first defined it. In 1991, more than 1,100 people attended the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in Washington, D.C to address environmental inequities across the United States and define the issues they were concerned about. At this event, the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice were created (First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, 1991). This event, which preceded the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), provided a basis for defining climate justice. A decade later, the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice were used as the basis for the 27 Bali Principles of Climate Justice (International Climate Justice Network, 2002). This brief history illustrates the significant role American grassroots organizations have played in shaping a global understanding of climate justice.

Bali Principle 7 states that environmental justice demands the right to participate as equal partners at every level of decision making. This principle can help us begin to think about what climate justice looks like. Additionally, Principle 7 helps us consider what climate justice learning might look like, in terms of what is learned, how it is assessed, and how curricula are planned and implemented.

The Mary Robinson Foundation, founded by former President of Ireland Mary Robinson a member of The Elders, an organization started by Nelson Mandela to foster issues of justice globally, has also contributed thinking to definitions of climate justice. In 2011 they developed basic principles of climate justice, specifically that climate justice is rooted in the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. As such climate justice centers the voices of those most vulnerable to climate change impacts to ensure that they are heard, their knowledge and experiences are prioritized, and their thoughts are acted upon. These principles also note that a vital aspect of any coherent approach to climate justice is an openness to partnership in an arrangement that is equitable.

Emerging from this historical foundation, some central themes around defining climate justice are clear. First, climate justice sits at the intersection of climate change and social justice. This means that climate change and climate science are not value-neutral but instead are connected to social issues in the world. Second, the mobilization of resources for climate mitigation and adaptation is an equity issue when it comes to who gets what resources. Third, climate justice is about networks for collective action, not only individual behavior change. Grassroots organizations, and community organizations and efforts, are at the heart of climate justice because they offer a collective voice that is more powerful than any individual voice and this collective voice is grounded in the real life opportunities and struggles of people in communities most impacted by climate and environmental injustices. Finally, climate justice involves equitable participation in decision making, policy development, and implementation, including in the field of education.

Thus from a climate justice perspective within education, we can ask: Who is deciding what is being learned and how it is being learned? Who is at the table to make those decisions? Climate justice teaching and learning is about transformation and participation, and how we learn together in doing that. With a focus on disproportionate impacts of climate change on vulnerable and marginalized groups, and future generations, climate justice is often defined as what is missing based on how these frontline communities are more negatively impacted. However, Communities of Color and other heavily impacted groups have a wealth of knowledge, understandings, and resources that need to be brought into educational work. Those on the frontlines of climate change do not need to be saved, they do not need anybody’s pity; they need to be adequately resourced, engaged in ethical and equitable partnerships, and be equitably involved in decision making processes.

In her book Mind, Culture, and Activity (2004), Barbara Rogoff, a leading learning scientist, defines learning as “…a process of transformation of participation itself” and notes that “… how people develop is a function of their transforming roles and understanding in the activities in which they participate.” This is very much what the environmental justice and climate justice communities are asking for; changes in participation, improved access for youth into STEM careers, improved involvement in local decision making, and the authority to shift money and resources toward things that are central to community interests.

Why Teach “Through” Climate Justice?

Our students are the Climate Generation (Jaquette Ray, 2020). Most were born into a world in which the climate was already changing. To them, the connections between climate impacts and social inequity are clear. They are the most ethnically diverse of all time, and face some of the greatest challenges in human history: global climate and environmental change as it intersects with socioeconomic and racial inequity. Their Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) education needs to be relevant to the scale and complexity of the problems they face. It needs to equip them with disciplinary practice and scientific knowledge in partnership with the systems thinking skills, critical consciousness, and civic engagement tools needed to leverage STEM to create societal change and improve their communities. Centering social justice issues, such as climate justice, in STEM classrooms broadens the participation of women and racial and ethnic groups that have been historically underrepresented in STEM fields. Over the past few decades, the STEM education community has awakened to the idea that the content and skills we teach in our courses must be humanized and taught in a context that is relevant to students’ interests, experiences, identities, and communities. This brings meaning to seemingly abstract and disparate STEM knowledge and skills. Such work has been happening, in parallel and sometimes in collaboration, at both the K-12 level and in higher education.

The National Research Council, in its A Framework for K-12 Science Education (Framework; 2012), provided a strong entry point for bringing climate justice education into K-12 STEM teaching and learning. In particular, Chapter 11 deserves a read as it provides research and background on equity within STEM education. The Framework authors provide a grounded vision of equitable STEM education, such that “…all students are provided with equitable opportunities to learn science and become engaged in science and engineering practices…,” with a recognition that “…connecting to students’ interests and experiences is particularly important for broadening participation in science” (p. 28).

Teaching climate justice in STEM courses, and especially the gateway courses of mathematics and chemistry, offers learning spaces and authentic opportunities for meeting students where they are at by providing meaningful learning that connects to their interests, experiences, communities, and identities. We cannot teach STEM in a neutral, disconnected way, because it does not have meaning for students; students lives and science itself are connected to human socio-political activities and experiences. Science learning, and science itself, is a cultural activity. We want students to see STEM in their everyday experiences and it is our job as educators to help them make connections between their lives and seemingly abstract STEM content and skills.

Higher education has come to a similar realization, albeit in a more disconnected way. A SENCER evaluation showed that students who took SENCER courses, in which STEM was taught through complex unresolved social issues with a focus on civic involvement and democratic processes, learned more STEM content, were more interested in STEM, and more capable of relating it to real world problems (Weston et al 2006). They also found that gains in science literacy were particularly pronounced for women and other racial and ethnic groups underrepresented in STEM.

A transformation of STEM culture away from an economic workforce focus, toward socially-relevant civic issues, is needed to attract and retain these groups and make STEM relevant to 21st century challenges. A shifted focus on social and civic issues as part of an equitable STEM curriculum is illustrated by a quote by a high-performing Black male student who left an engineering major:

“A big concern of a lot of Black students is we feel like we’re being prepared to go into white corporate America, and it won’t really help our community—we won’t have the opportunity through our careers to give back to the community. Anything that we do for the community would be outside of our academic field, and that’s a very serious concern.” (Seymour & Hewitt, 1997, p. 337)

More than 20 years later Seymour & Hewitt (2019) reconfirmed similar values at play: 73% and 60% of women and racially and ethnically diverse students, respectively, who switched out of STEM majors had altruistic career intentions. Co-authors Remington Doucette and Price regularly receive similar feedback from their diverse community college students regarding their climate justice lessons. A Black woman in Price’s class recently expressed thanks:

“…for teaching me chemistry the way it should be taught with real life reference and practicality. I have been accepted to UW Chem E [University of Washington Chemical Engineering]. I can’t wait to be a part of the problem solving community and hopefully come up with solutions to combat the climate crisis.” (Personal Communication, February 2020)

These findings are echoed by a recent study about the Equity Ethic, a concept developed at Vanderbilt University (McGee & Bentley, 2017). The Equity Ethic focuses on “students’ principled concern for social justice” (p. 6) and explains why a social justice-centered approach to STEM teaching may be more appealing to groups typically underrepresented in STEM fields, particularly Students of Color and women. Patterson Williams & Grey (2013) offer excellent examples of how the Equity Ethic may be operationalized in the classroom, with social justice as a meaningful phenomena for investigation using STEM knowledge and skills. Bringing social justice issues into the classroom brings real-world issues into the classroom that connect with students’ identities and communities, which is one of eight core competencies for culturally responsive teaching (Muñiz, 2020). Furthermore, real-world issues focused specifically on social justice are part of educational equity in the STEM curriculum. Social Justice Education (SJE) is one of the three key areas of instructional equity (Hammond, 2015; Hammond, 2020).

A social justice approach to STEM teaching, rooted in climate justice, will resonate with most students. Two recent Pew Research Center polls found much higher concern about climate change in people ages 18 to 39, compared to their elders, even for youth with more conservative social and political leanings (PRC, 2020; PRC, 2022). This quote, by a White male student, who took Remington Doucette’s chemistry course to transition from a career in big tech to a career in medicine, illustrates that students want and demand this type of STEM education:

“I think if I remained in the big-tech-world and didn’t take your class, I wouldn’t have started thinking about these complicated health effects [related to climate impacts and fossil fuel burning] and general need for awareness. UW CS [University of Washington Computer Science] didn’t reveal any of this to me which is a bit annoying to me now. ”(Personal Communication, February 2021)

At their community colleges, Remington Doucette and Price implemented student surveys beginning in 2021 with faculty from several other STEM disciplines as part of an NSF IUSE grant focused on teaching climate justice in STEM. The preliminary survey results showed that the top three issues of concern about the world today for students are climate change, racial inequality, and mental health. About 60 % of students felt these issues were not addressed in their STEM courses, but almost 80 % want them addressed. Climate justice lies at the intersection of these issues. (For an introduction to mental health and climate, and what we can do about it, see Remington Doucette, 2021.)

Climate Justice in Community College STEM Learning: The C-JUSTICE Project

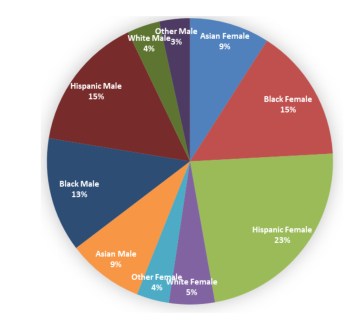

Climate Justice in Undergraduate STEM: Incorporating Civic Engagement (C-JUSTICE) aims to improve STEM education by supporting community college faculty as they create course modules that teach disciplinary content through climate justice and civic engagement, with a solutions focus and action orientation. The project aims to improve student learning, broaden participation of women and racial and ethnic groups underrepresented in STEM fields, and prepare citizens and scientists to deal with 21st century challenges. It is supported by an NSF IUSE grant. Since the project’s inception in 2021, course modules (C-JUSTICE modules) have covered a range of climate justice issues and have been implemented by 21 faculty across eight different STEM disciplines at Bellevue College (BC) and North Seattle College (NSC). (Table 1).

C-JUSTICE is based on a professional development curriculum for teaching climate justice and civic engagement across the curriculum developed at BC in 2017 and adopted by NSC in 2019. It is situated in two frameworks from STEM education practice and research: SENCER and the Equity Ethic. (Figure 1) SENCER provides a pedagogy for bringing complex unresolved societal issues into the classroom, whereas the Equity Ethic (McGee & Bentley, 2017) is more of a theory about why a social justice-centered approach to STEM teaching can be more appealing to groups typically underrepresented in STEM fields, particularly Students of Color and women. At its very heart, the Equity Ethic is about “students’ principled concern for social justice.” When students can see STEM as a means to promote social justice, help their communities (Elmi et al., 2022), and disrupt systems of oppression, then they are more likely to pursue a STEM major, stay in a STEM major, or end up in a STEM career. It is about transforming STEM culture away from a singular focus on workforce development and economics, toward a focus on socially relevant civic issues and democracy. C-JUSTICE modules aim to expose the social political context that students experience, raise consciousness about inequity in the world, and help students and faculty develop a “lens” for recognizing inequitable patterns and practices in society and develop the tools needed to interrupt them. A recent book by Eric Liu, You’re More Powerful Than You Think: A Citizen’s Guide to Making Change Happen (2017), provides frameworks and ideas for civic involvement being used by C-JUSTICE.

The three broad learning goals for C-JUSTICE modules are that they:

- make clear to students the intra- and inter-generational connections between climate change and racial, economic, gender, intergenerational, interspecies, and other injustices,

- foster the skills, knowledge, commitments, responsibilities, values, and efficacy (Figure 2; Wang & Jackson, 2005) as well as the actions needed to engage civically with a community beyond the classroom in a way that promotes collective systemic change, and

- highlight positive stories of change that make the world a more just and equitable place.

C-JUSTICE portrays intra-generational justice as a wedge (Figure 3), adapted from (Making Partners, 1988). The more vulnerable a person or group is, the more difficult it is going to be to deal with climate impacts. In the wedge, climate impacts are represented by the ball and vulnerabilities are the wedges. The more vulnerabilities, the steeper the ramp, the harder it is to handle climate impacts. Faculty in C-JUSTICE workshops find this wedge framework to be helpful for developing a “lens” or critical consciousness for recognizing inequities that arise from climate impacts.

C-JUSTICE portrays intra-generational justice as a wedge (Figure 3), adapted from (Making Partners, 1988). The more vulnerable a person or group is, the more difficult it is going to be to deal with climate impacts. In the wedge, climate impacts are represented by the ball and vulnerabilities are the wedges. The more vulnerabilities, the steeper the ramp, the harder it is to handle climate impacts. Faculty in C-JUSTICE workshops find this wedge framework to be helpful for developing a “lens” or critical consciousness for recognizing inequities that arise from climate impacts.

Preliminary C-JUSTICE student survey data collected at BC and NSC are compelling (Remington Doucette and Price, unpublished). They show that top issues for students are climate change, racial inequality, and mental health and that students want these issues taught in their courses. Most have a desire to be more socially, politically, and civically engaged in their communities, but are not presently engaged because they don’t know how. Finally, students agree about the need for equity, but there are gaps in their understanding of the systemic causes.

Survey data also showed that after experiencing a C-JUSTICE module in a STEM course, more students see STEM as a tool for achieving social justice and that it can be used to help solve problems in communities they care about and serve racially and economically marginalized communities. They also have a much greater understanding of climate justice and know how to become involved. More students also see STEM as useful for informing and taking civic action, and they intend to become more involved in their communities. Finally, learning STEM in the context of climate justice increased their interest in STEM and their motivation to learn STEM.

Beyond the efforts at BC and NSC, this work is being disseminated to 34 community and technical colleges (CTCs) across Washington state through a Climate Solutions effort led by the State Board of Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC) and funded at $1.5 million by the WA state legislature (Washington SBCTC, 2022). On average, more than 320,000 students enroll in a community or technical college across the state per year. More than half of those students are Students of Color. With statewide coordination and resources supporting this climate solutions effort, systemic inequities can be overcome to empower Students of Color from frontline communities who, due to structural racism, disproportionately experience the burdens and risks of a changing climate, are the least economically resourced to enact change in their communities and are the most excluded from the benefits from the green economy. Utilizing this specific educational lever for systemic change—expanding climate solutions education and green workforce development in CTCs and making our colleges more sustainable—has the greatest potential to increase equity in all areas—in higher education, in the workforce and economy, and in frontline communities across the state of Washington. This work expands climate solutions education and green workforce development to ensure that all people can be sustainability and equity minded leaders in their communities and professions, can respond to the impacts of a changing environment, benefit from the green economy, and can contribute to community-based and industry-led climate solutions.

The SBCTC is working to integrate climate solutions education into curricula, align green workforce development programs with climate solutions, and develop a system-wide climate action plan. The SBCTC’s goal is to promote greater economic vitality in the green workforce for the state of Washington, generate community based climate solutions, and make CTCs in Washington state more sustainable. It has four focus areas: Climate Solutions Education, Green Workforce Development, Sustainability Colleges, and Centering Equity. The climate justice faculty professional development (PD) curriculum developed by BC and NSC, both across the curriculum and as part of C-JUSTICE, is being integrated into the Climate Solutions Education focus area. The goals of this focus area are to establish faculty leadership, provide training and PD for college faculty and staff to develop integrated curricula across disciplines, in concert with local community-based organizations, employers, and tribal communities that address the needs of frontline communities and support students in building the problem solving, social justice, and civic engagement related skills to be climate solutions leaders in their fields.

Resources for Engaging in Climate Justice Teaching and Learning

How can we teach climate justice in STEM? In order to resource learning in the areas of STEM, equity, climate change, and climate justice, there is a demand for resources to help address emerging questions of practice. Several initiatives have been working to provide such resources across the United States including: the STEM Teaching Tools and the CLEAN Network.

The STEM Teaching Tools collection, initiated in 2014 by the Institute of Science and Math Education at the University of Washington, provides such learning supports. In the last few years, more of the STEM Teaching Tools resources have centered around issues of climate learning with a justice lens, as educators have expressed increasing needs for resources in this area. Additionally, resources that help educators communicate with families and administrators, engage with communities, and foster more equitable place-based learning opportunities that center sustainability or climate mitigation and adaptation efforts are also in need. All these resources are being developed in collaboration with educators, researchers, and community organizations working at the intersection of climate change education, spanning K-12 to higher education contexts. A special mention should be made of the Washington State ClimeTime effort and the more recent Climate Teacher Education Collaborative, that have brought those involved in climate change education in the state together in deep collaboration with the Institute of Science and Math Education to foster resources for use in diverse socio-political teaching contexts.

The CLEAN Network, which stands for the Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network, began building resources in 2010 as part of the National Science Digital Library Pathways project work. Today the CLEAN Network provides extensive scientist and educator vetted resources on climate change learning, teacher learning resources on climate change science and age-appropriate equitable pedagogies, and a community of practice to connect those engaged in climate change education nationally. The Institute of Science and Math Education has been in partnership with CLEAN for the last five years around resource development collaborations and these two organizations continue to seek co-generative opportunities to collaboratively build and resource the capacity of educators seeking to learn and implement climate change related education.

The teaching of climate justice in STEM is rapidly expanding, yet the disparate pockets of climate justice STEM teaching resources can be difficult to locate. In 2021, the National Science Teaching Association published a Special Issue on Climate Change (NSTA, 2021). This is one of the best set of STEM-specific climate justice examples to date for K-12. Other resources emerging from the C-JUSTICE project, developed at the community college level, will be published in the form of course modules within the next two years to the Curriculum for the Bioregion’s Activity Collection on Carleton College’s Science Education Resource Center (SERC) site. There is currently one existing STEM-specific climate justice module for General Chemistry focused on systems thinking and civic engagement around CO2 and PM 2.5 emissions from coal combustion in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Strategies for Engaging in Climate Justice Teaching and Learning

When planning out climate justice teaching, there are three principles that are important to keep in mind. First is the idea of nurturing hope and action. In order to help students, and ourselves, work through the feelings of despair that come along with learning about climate justice issues, we must teach climate justice within a solution-centered or action-centered framework. This means starting with and focusing on solutions or actions, rather than tacking them on in a very small way to the end of a climate justice lesson that is mostly focused on the problem. For example, starting with alternative energy and having students analyze the social impacts of one particular form of alternative energy over another. Centering teaching around phenomena such as alternative energy centers both the STEM issues and the social issues. The People’s Curriculum for the Earth is a social studies curriculum that STEM educators in Washington State have begun to draw from to think about how to teach STEM within the context of a complex, unresolved societal issue and social phenomena.

The second major principle is addressing controversy and indoctrination. Talking about social issues in the STEM classroom seems out of bounds for many educators. However, it is important to understand that climate change is not a scientific controversy. While there may be some areas of the science and technology that emerge as undecided and lacking consensus, such as alternative energy, there is scientific consensus about the fact that climate change is human-caused. Therefore, the controversy is around social solutions, not climate science. If we accept that humans cause climate change, then we need to accept that humans must find solutions and that solutions often have economic, political, and social repercussions. These are the things that are controversial. If we don’t acknowledge and name the economic, political, and social controversies in our teaching, then students get confused about where the controversy actually lies. As part of bringing these controversies into our classrooms, we need to address issues of equity because those social and historical understandings of past inequities are built into the system due to our use of petroleum products. For example, the environmental justice impacts that have long been documented in Cancer Alley in Texas and Louisiana caused by the petrochemical industry are now being amplified by climate change.

A third principle is age-appropriate climate learning. We cannot talk to a 7-year-old about climate change in the same way we would talk to an adult. Some resources for finding age-appropriate climate learning include Talk Climate, the Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network (CLEAN), and the STEM Teaching Tools developed at the University of Washington.

There is no universal curriculum resource for climate justice—instead learning needs to be contextualized for local places and social contexts in collaboration with community members and organizations. We often make assumptions about what a given community knows or is interested in, but instead of making these assumptions we need to engage in conversation with community members and organizations. This will help us center inquiry-based phenomena that they will be interested in investigating. Washington State’s ClimeTime initiative provides “Portraits of Projects” and other Open Educational Resources (OERs) where you can find examples of how climate justice learning is being designed in and with the community to be adaptive to local contexts. The ClimeTime Portraits and OERs provide examples of the challenges faced by educators when engaging with local issues and communities and how they addressed those challenges. It is important to think about local context when teaching about climate justice, such as focusing on a green transition and jobs or regenerative agriculture or sustainability forestry rather than social justice in some regions.

It is also important that educators are supported to understand and implement culturally responsive learning practices. While no universal culturally responsive climate justice curriculum exists, it is important to provide resources for professional learning, climate change education, and community conversations. Learning in Places is rooted in indigenous knowledge and environmental justice, and have very helpful resources for elementary and secondary educators.

STEM Teaching Tools is funding teachers and community partners to write resources describing tips and resources for teaching about climate, how to work with community partners, and how to build supports with administrators and families. These resources are freely available online, to make sure that everyone has access to high-quality teaching materials (STEM Teaching Tools, 2022; Elmi et al., 2022). STEM Teaching Tools has pulled together Climate Learning Resources that are grounded in culturally-responsive and justice-centered pedagogies, including videos of seminars, into a single portal to make information easier to locate and use.

CLEAN provides an incredible breadth of resources and examples to learn about climate science, including principles of climate science literacy. CLEAN is building resources to help facilitate age-appropriate instruction, teacher learning about climate change, and student learning about climate change concepts. Talking about climate justice, learning climate science, and working with local communities to lift ways they are engaging in climate change mitigation and adaptation are all critical aspects of localized justice-centered climate learning.

There is an enormous amount of climate science to learn and professionals also need help in how to share climate information in ways that minimize emotional harm and empower learners. Talk Climate is a community organization that seeks to address this need. The Talk Climate community organization brings together educators, mental and medical health professionals, youth activists, artists, and climate scientists to create and share resources and publications on age appropriate ways for teachers, parents, and other professionals who work with young people, to share climate information with age and emotional development in mind.

Conclusion

Climate justice is justice for everyone on Earth. Finding a sustainable future where we are not at war with each other, where we have balance and equity, is our shared future. Justice is not something for someone else alone. It is our shared future. It is our students’ future. We need to raise their awareness about the risks and vulnerabilities they will face, and empower them with the knowledge and tools they will need to adapt to and mitigate the climate crisis and nurture climate justice.

About the Authors

Sonya Remington Doucette is a sustainability leader at Bellevue College, where she is Chair of the Sustainability Curriculum Committee and the Sustainability Concentration Coordinator. She is the author of Sustainable World: Approaches to Analyzing and Resolving Wicked Problems (2017), which is used by institutions at the cutting edge of sustainability in higher education Prior to BC, she was a Senior Lecturer in the School of Sustainability at Arizona State University. She has also conducted sustainability education research at ASU. Two of her manuscripts were highly commended as Outstanding Papers in the International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education’s Annual Awards for Excellence. From 2008 -10, she was a post-doctoral teaching fellow in the Program on the Environment at the University of Washington. She began her academic sustainability career in 2007 when she became active in the Curriculum for the Bioregion (C4B) initiative at Evergreen State College. C4B seeks to infuse sustainability into all curricula, in all disciplines, at institutions of higher education in Washington State.

Sonya Remington Doucette is a sustainability leader at Bellevue College, where she is Chair of the Sustainability Curriculum Committee and the Sustainability Concentration Coordinator. She is the author of Sustainable World: Approaches to Analyzing and Resolving Wicked Problems (2017), which is used by institutions at the cutting edge of sustainability in higher education Prior to BC, she was a Senior Lecturer in the School of Sustainability at Arizona State University. She has also conducted sustainability education research at ASU. Two of her manuscripts were highly commended as Outstanding Papers in the International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education’s Annual Awards for Excellence. From 2008 -10, she was a post-doctoral teaching fellow in the Program on the Environment at the University of Washington. She began her academic sustainability career in 2007 when she became active in the Curriculum for the Bioregion (C4B) initiative at Evergreen State College. C4B seeks to infuse sustainability into all curricula, in all disciplines, at institutions of higher education in Washington State.

Heather U. Price earned her Ph.D. in Analytical and Environmental Chemistry studying the long-range transport and photochemistry of air pollution. Her postdoctoral atmospheric chemistry research was conducted with the Program on Climate Change at University of Washington, incorporating the isotopes of hydrogen into a global chemical transport model of the atmosphere. She has developed a number of courses on climate change: for undergraduate students at UW, a summer program for high school students, continuing science education courses for elementary and 6-12 grade teachers. Her latest research and teaching focus is the development of short courses and workshops for faculty to help them incorporate climate justice with civic and/or community engagement into their existing STEM, arts, and humanities curriculum. She is also on the leadership team of the Seattle 500 Women Scientists organization and is co-founder of the climate resources community hub, TalkClimate.org.

Heather U. Price earned her Ph.D. in Analytical and Environmental Chemistry studying the long-range transport and photochemistry of air pollution. Her postdoctoral atmospheric chemistry research was conducted with the Program on Climate Change at University of Washington, incorporating the isotopes of hydrogen into a global chemical transport model of the atmosphere. She has developed a number of courses on climate change: for undergraduate students at UW, a summer program for high school students, continuing science education courses for elementary and 6-12 grade teachers. Her latest research and teaching focus is the development of short courses and workshops for faculty to help them incorporate climate justice with civic and/or community engagement into their existing STEM, arts, and humanities curriculum. She is also on the leadership team of the Seattle 500 Women Scientists organization and is co-founder of the climate resources community hub, TalkClimate.org.

Deb L. Morrison works at the intersection of justice, climate science, and learning. She is a climate and anti-oppression activist, scientist, learning scientist, educator, mother, locally elected official, and many other things besides. Deb works in research-practice-policy partnerships from local community to international scales. She works to iteratively understand complex socio-ecological systems through design-based and action oriented research while at the same time seeking to improve human-environment relationships and sustainability. Dr. Morrison draws on an eclectic range of justice theory to inform her work in the world and to foster her continued journey for transformative liberation. She is a well-published author on diverse topics that intersect with climate justice learning and continues to foster collaborative writing partnerships across disciplines and communities that have historically been disconnected. Information about Dr. Morrison’s work can be found at www.debmorrison.me.

Deb L. Morrison works at the intersection of justice, climate science, and learning. She is a climate and anti-oppression activist, scientist, learning scientist, educator, mother, locally elected official, and many other things besides. Deb works in research-practice-policy partnerships from local community to international scales. She works to iteratively understand complex socio-ecological systems through design-based and action oriented research while at the same time seeking to improve human-environment relationships and sustainability. Dr. Morrison draws on an eclectic range of justice theory to inform her work in the world and to foster her continued journey for transformative liberation. She is a well-published author on diverse topics that intersect with climate justice learning and continues to foster collaborative writing partnerships across disciplines and communities that have historically been disconnected. Information about Dr. Morrison’s work can be found at www.debmorrison.me.

Irene Shaver is the newly appointed Program Manager of the Climate Solutions Program at the Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges. The program focuses on climate solutions education across the curriculum, green workforce development, and making our colleges more sustainable. This program has several opportunities this year for community and technical colleges to deepen their work in sustainability and climate education that she will share. Shaver spent six years at Bellevue College working as a program manager for undergraduate research, and also was a high school teacher in Idaho, and worked at the Institute of Community Research in Connecticut as a program coordinator. She earned her doctorate in environmental science and sociology from the University of Idaho.

Irene Shaver is the newly appointed Program Manager of the Climate Solutions Program at the Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges. The program focuses on climate solutions education across the curriculum, green workforce development, and making our colleges more sustainable. This program has several opportunities this year for community and technical colleges to deepen their work in sustainability and climate education that she will share. Shaver spent six years at Bellevue College working as a program manager for undergraduate research, and also was a high school teacher in Idaho, and worked at the Institute of Community Research in Connecticut as a program coordinator. She earned her doctorate in environmental science and sociology from the University of Idaho.

Acknowledgement

Much of this work was funded by an NSF IUSE grant (NSF DUE 2043535).

References

Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network (CLEAN). (2022). https://cleanet.org/index.html

ClimeTime. (2022). Climate Science Learning Initiative, https://www.climetime.org/

Elmi, I., Harper, T., Slade, M., & Price, H. (2022). Let’s Talk Climate! Bridging Climate Justice Learning and Action Across School, Home, and Community, STEM Teaching Tool #84, , Seattle, WA: Institute of Science and Math Education, University of Washington, Retrieve from: https://stemteachingtools.org/brief/84

First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. (1991). The Principles of Environmental Justice (EJ). Defined by delegates to the summit held October 24027, 1991 in Washington, DC. Retrieve from: https://www.ejnet.org/ej/principles.pdf

Hammond, Z. (2020). A conversation about instructional equity with Zaretta Hammond, Collaborative Classroom, Retrieve from: https://www.collaborativeclassroom.org/blog/instructional-equity-with-zaretta-hammond/)

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

International Climate Justice Network. (2002) Bali Principles of Climate Justice. Created by delegates to the preparatory meeting for the Earth Summit held in Bali, Indonesia, August 2002. Retrieved from: https://www.corpwatch.org/article/bali-principles-climate-justice

Jaquette Ray, S. (2020). A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet, Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Mary Robinson Foundation. (2011). Principles of Climate Justice, Adopted by the Mary Robinson Foundation in August 2011, Retrieve from: https://www.mrfcj.org/principles-of-climate-justice/

McGee, E., & Bentley, L. (2017). The Equity Ethic: Black and Latinx College Students Reengineering Their STEM Careers Toward Justice, American Journal of Education, 124: 1-36.

Muñiz, J. (2020). Culturally Responsive Teaching: A Reflection Guide, Policy Paper, New America, Retrieve from: https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/policy-papers/culturally-responsive-teaching-competencies/

National Research Council. (2012). A Framework for K-12 Science Education, Next Generation Science Standards. https://www.nextgenscience.org/framework-k-12-science-education

National Science Teaching Association. (2021). Climate Change (Special Issue), Connected Science Learning, 3(5), Retrieve from: https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-september-october-2021

Patterson Williams, A., & Gray, S. (2013). Social justice issues as phenomena. Next Generation Science Standard panel discussion, Retrieve from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=IkiF-qDqUx4

Pew Research Center. (2022). Younger evangelicals in the U.S. are more concerned than their elders about climate change. Retrieve from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/12/07/younger-evangelicals-in-the-u-s-are-more-concerned-than-their-elders-about-climate-change/

Pew Research Center. (2020). Millenial and Gen Z Republicans stand out from their elders on climate and energy issues. Retrieve from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/24/millennial-and-gen-z-republicans-stand-out-from-their-elders-on-climate-and-energy-issues/

Remington Doucette. S. (2021). Hope is Not Optional: Managing Emotions in a Changing World, A Climate Justice Case Study, Bellevue College Opening Day Session, Retrieve from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hYZe1fB4mE4

Remington Doucette, S. (2022). Systems thinking and civic engagement for climate justice in General Chemistry: CO2 and PM 2.5 pollution from coal combustion, Curriculum for the Bioregion Activity Collection, Science Education Resource Center (SERC), Carleton College, Retrieve from: https://serc.carleton.edu/bioregion/examples/247629.html)

Rethinking Schools. (2014). A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching Climate Change and the Environmental Crisis, B. Bigelow & T. Swinehart (Editors). Portland, OR: A Rethinking Schools Publication, Retrieve from: https://rethinkingschools.org/books/a-people-s-curriculum-for-the-earth/

SERC. (2022). Carleton College Science Education Resource Center, https://serc.carleton.edu/index.html

Seymour, E., & Hunter, A.B. (2019). Talking About Leaving Revisited: Persistence, Relocation, and Loss in Undergraduate STEM Education. Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Seymour, E., & Hewitt, N. M. (1997). Talking About Leaving: Why Undergraduates Leave the Sciences, Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

STEM Teaching Tools. (2022). Teaching Tools for Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) Education, Retrieve from: https://stemteachingtools.org/

Talk Climate. (2022). Retrieve from: https://talkclimate.org/

Wang, Y. & G. Jackson. (2005). Forms and Dimensions of Civic Involvement, Michigan Journal of Community and Service Learning, Spring 2005 Issue, Retrieve from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ848471.pdf

Washington State Board of Community and Technical Colleges. (2022). Climate Solutions Program. Retrieve from: https://www.sbctc.edu/colleges-staff/grants/climate-solutions

Weston, T., Seymour, E., & Thirty, H. (2006) Evaluation of Science Education for New Civic Engagements and Responsibilities (SENCER) Project. Retrieve from: http://sencer.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/FINAL_REPORT_SENCER_12_21_06.pdf

Download the article

Guang Jin (Sc.D. in Environmental Health Sciences) is Professor of Environmental Health & Sustainability in the Department of Health Sciences at Illinois State University, with areas of expertise and experience in pollution prevention, biomass energy, and sustainability.

Guang Jin (Sc.D. in Environmental Health Sciences) is Professor of Environmental Health & Sustainability in the Department of Health Sciences at Illinois State University, with areas of expertise and experience in pollution prevention, biomass energy, and sustainability. Thomas Bierma (Ph.D. in Public Health) is Emeritus Professor of Environmental Health & Sustainability in the Department of Health Sciences at Illinois State University, with research experience in sustainable business practices, bioenergy, waste management, and pedagogy for higher education.

Thomas Bierma (Ph.D. in Public Health) is Emeritus Professor of Environmental Health & Sustainability in the Department of Health Sciences at Illinois State University, with research experience in sustainable business practices, bioenergy, waste management, and pedagogy for higher education.

Sandie Han is a Professor of Mathematics at New York City College of Technology. She has extensive experience in program design and administration, including serving as the mathematics department chair for six years, PI on the U.S. Department of Education MSEIP grant and Co-PI on the NSF S-STEM grant. Her research area is number theory and mathematics education.

Sandie Han is a Professor of Mathematics at New York City College of Technology. She has extensive experience in program design and administration, including serving as the mathematics department chair for six years, PI on the U.S. Department of Education MSEIP grant and Co-PI on the NSF S-STEM grant. Her research area is number theory and mathematics education. Diana Samaroo is a Professor in the Chemistry Department at NYC College of Technology in Brooklyn, New York.

Diana Samaroo is a Professor in the Chemistry Department at NYC College of Technology in Brooklyn, New York.  Janet Liou-Mark was a Professor Emeritus of Mathematics at NYC College of Technology. Her research interests included peer-led team learning, mentoring, interdisciplinary learning, and enhancing diversity in STEM. Dr. Liou-Mark received thirteen awards for her excellence in education, which included the 2011 CUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Mathematics Instruction and the Mathematical Association of America Metropolitan New York Section 2014 Award for Distinguished Teaching of Mathematics.

Janet Liou-Mark was a Professor Emeritus of Mathematics at NYC College of Technology. Her research interests included peer-led team learning, mentoring, interdisciplinary learning, and enhancing diversity in STEM. Dr. Liou-Mark received thirteen awards for her excellence in education, which included the 2011 CUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Mathematics Instruction and the Mathematical Association of America Metropolitan New York Section 2014 Award for Distinguished Teaching of Mathematics. Lauri Aguirre is the Director of First Year Programs (FYP) at New York City College of Technology. In this role, she has administered and designed programs for new students, focusing on their acclimatization of basic academic skills, college preparedness and student success. Programming has included the First Year Summer Program immersion courses and workshops in English and mathematics, First Year Learning Communities, City Tech 101: A Student Success Workshop, the FYP Peer Mentoring program, and the student handbook, The Companion for the First Year at City Tech.

Lauri Aguirre is the Director of First Year Programs (FYP) at New York City College of Technology. In this role, she has administered and designed programs for new students, focusing on their acclimatization of basic academic skills, college preparedness and student success. Programming has included the First Year Summer Program immersion courses and workshops in English and mathematics, First Year Learning Communities, City Tech 101: A Student Success Workshop, the FYP Peer Mentoring program, and the student handbook, The Companion for the First Year at City Tech.

In response to the question “Do you plan to share this information with friends, family or others?” 56 respondents indicated “yes,” nine indicated “no,” and 11 did not respond to the question.

In response to the question “Do you plan to share this information with friends, family or others?” 56 respondents indicated “yes,” nine indicated “no,” and 11 did not respond to the question. Jacqueline Curnick is the Program Coordinator of the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center Community Engagement Core at the University of Iowa. She holds a Master of Sustainable Development Practice with a focus in environmental communication.

Jacqueline Curnick is the Program Coordinator of the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center Community Engagement Core at the University of Iowa. She holds a Master of Sustainable Development Practice with a focus in environmental communication. Brandi Janssen is a Clinical Associate Professor of Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of Iowa. She directs Iowa’s center for Agricultural Safety and Health (I-CASH) and the Community Engagement Core for the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (EHSRC).

Brandi Janssen is a Clinical Associate Professor of Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of Iowa. She directs Iowa’s center for Agricultural Safety and Health (I-CASH) and the Community Engagement Core for the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (EHSRC).

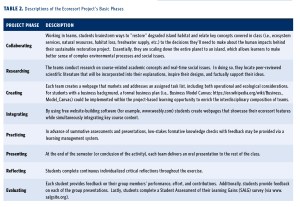

This activity is applicable to a wide range of disciplines and academic levels (Table 3), and instructors can incorporate the activity in multiple ways. For example, they might

This activity is applicable to a wide range of disciplines and academic levels (Table 3), and instructors can incorporate the activity in multiple ways. For example, they might

David Green specializes in advancing learner-centered curricula in health sciences, medical education, and STEM education.

David Green specializes in advancing learner-centered curricula in health sciences, medical education, and STEM education.

Steven Bachofer teaches chemistry and environmental science at Saint Mary’s College and has worked with the Alameda Point Collaborative for more than 15 years through his affiliation with the SENCER project. He has also co-authored a SENCER model course with Phylis Martinelli, addressing the redevelopment of a Superfund site (NAS Alameda).

Steven Bachofer teaches chemistry and environmental science at Saint Mary’s College and has worked with the Alameda Point Collaborative for more than 15 years through his affiliation with the SENCER project. He has also co-authored a SENCER model course with Phylis Martinelli, addressing the redevelopment of a Superfund site (NAS Alameda).  Marque Cass has been in the field of education since before his graduation from UC-Davis, where he earned a BS in Community and Regional Development with an emphasis in Organization and Management. Since January 2019, he has been the youth program coordinator for Alameda Point Collaborative, doing mentoring and advocacy work for formerly homeless families. More recently, he has been elected a community partner liaison with Saint Mary’s College, working to help create stronger networks between organizations.

Marque Cass has been in the field of education since before his graduation from UC-Davis, where he earned a BS in Community and Regional Development with an emphasis in Organization and Management. Since January 2019, he has been the youth program coordinator for Alameda Point Collaborative, doing mentoring and advocacy work for formerly homeless families. More recently, he has been elected a community partner liaison with Saint Mary’s College, working to help create stronger networks between organizations. Laura B. Liu, Ed.D. is an assistant professor and Coordinator of the English as a New Language (ENL) Program in the Division of Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus (IUPUC). Her research and teaching include the integration of civic science and funds of knowledge into elementary and teacher education curricula and instruction.

Laura B. Liu, Ed.D. is an assistant professor and Coordinator of the English as a New Language (ENL) Program in the Division of Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus (IUPUC). Her research and teaching include the integration of civic science and funds of knowledge into elementary and teacher education curricula and instruction. Taylor Russell is an elementary teacher and earned her Bachelor of Science in Elementary Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus (IUPUC), with a dual license in teaching English as a New Language (ENL).

Taylor Russell is an elementary teacher and earned her Bachelor of Science in Elementary Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus (IUPUC), with a dual license in teaching English as a New Language (ENL).

Diana Samaroo is a professor in the Chemistry Department at NYC College of Technology in Brooklyn, New York.

Diana Samaroo is a professor in the Chemistry Department at NYC College of Technology in Brooklyn, New York.  Liana Tsenova is a professor emerita in the Biological Sciences Department at the New York City College of Technology. She earned her MD degree with a specialty in microbiology and immunology from the Medical Academy in Sofia, Bulgaria. She received her postdoctoral training at Rockefeller University, New York, NY. Her research is focused on the immune response and host-directed therapies in tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. Dr. Tsenova has co-authored more than 60 publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals and books. At City Tech she has served as the PI of the Bridges to the Baccalaureate Program, funded by NIH. She was a SENCER leadership fellow. Applying the SENCER ideas, she mentors undergraduates in interdisciplinary projects, combining microbiology and infectious diseases with chemistry and mathematics, to address unresolved epidemiologic, ecologic, and healthcare problems.

Liana Tsenova is a professor emerita in the Biological Sciences Department at the New York City College of Technology. She earned her MD degree with a specialty in microbiology and immunology from the Medical Academy in Sofia, Bulgaria. She received her postdoctoral training at Rockefeller University, New York, NY. Her research is focused on the immune response and host-directed therapies in tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. Dr. Tsenova has co-authored more than 60 publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals and books. At City Tech she has served as the PI of the Bridges to the Baccalaureate Program, funded by NIH. She was a SENCER leadership fellow. Applying the SENCER ideas, she mentors undergraduates in interdisciplinary projects, combining microbiology and infectious diseases with chemistry and mathematics, to address unresolved epidemiologic, ecologic, and healthcare problems. Sandie Han is a professor of mathematics at New York City College of Technology. She has extensive experience in program design and administration, including service as the mathematics department chair for six years, PI on the U.S. Department of Education MSEIP grant, and co-PI on the NSF S-STEM grant. Her research area is number theory and mathematics education.

Sandie Han is a professor of mathematics at New York City College of Technology. She has extensive experience in program design and administration, including service as the mathematics department chair for six years, PI on the U.S. Department of Education MSEIP grant, and co-PI on the NSF S-STEM grant. Her research area is number theory and mathematics education. Urmi Ghosh-Dastidar is the coordinator of the Computer Science Program and a professor in the Mathematics Department at New York City College of Technology – City University of New York. She received a PhD in applied mathematics jointly from the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University and a BS in applied mathematics from The Ohio State University. Her current interests include parameter estimation via optimization, infectious disease modeling, applications of graph theory in biology and chemistry, and developing and applying bio-math related undergraduate modules in various SENCER related projects. She has several publications in peer-reviewed journals and is the recipient of several MAA NREUP grants, a SENCER leadership fellowship, a Department of Homeland Security grant, and several NSF and PSC-CUNY grants/awards. She also has extensive experience in mentoring undergraduate students in various research projects.

Urmi Ghosh-Dastidar is the coordinator of the Computer Science Program and a professor in the Mathematics Department at New York City College of Technology – City University of New York. She received a PhD in applied mathematics jointly from the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University and a BS in applied mathematics from The Ohio State University. Her current interests include parameter estimation via optimization, infectious disease modeling, applications of graph theory in biology and chemistry, and developing and applying bio-math related undergraduate modules in various SENCER related projects. She has several publications in peer-reviewed journals and is the recipient of several MAA NREUP grants, a SENCER leadership fellowship, a Department of Homeland Security grant, and several NSF and PSC-CUNY grants/awards. She also has extensive experience in mentoring undergraduate students in various research projects.