Abstract

Science Cafés are informal community gatherings that aim to facilitate the engagement of scientific researchers with the general public. These events have been implemented worldwide in rural and urban settings. This article evaluates two Science Café series, held in rural Iowa communities. Evaluation of Science Cafés typically consists of participant surveys to measure satisfaction with the presenter, interest in the topic, or solicit topic suggestions for future events. This paper presents results from a qualitative evaluation that aimed to better understand how the information presented at Science Cafés was shared with others in the community following the event. Results suggest that participants share information in both formal and informal settings following a Science Café, especially those who self-identify as “champions” of an issue. This research suggests that future evaluations examine rural social networks to better understand the broader community impact of these events.

Introduction

Science Cafés are informal community gatherings that aim to facilitate the engagement of scientific researchers with the general public. These events have been implemented worldwide in rural and urban settings. The University of Iowa’s Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (EHSRC) has hosted Science Cafés since 2013, mostly in rural communities in Iowa. Evaluation of Science Cafés typically consists of participant surveys to measure satisfaction with the presenter and interest in the topic or to solicit topic suggestions for future events. This paper presents results from a qualitative evaluation that aimed to better understand how the information presented at Science Cafés was shared with others in the community following the event.

Background

Science Cafés are casual events designed to engage members of the public with science and scientists. These interactive gatherings can be in a coffee house, bar, library, or community space. They typically involve a presentation by one or more speakers with a scientific research background, followed by a group discussion and questions (NOVA Education, 2020). The bi-directional communication, in which audience members discuss the topic and pose questions, allows researchers to learn about public perceptions, concerns, and curiosity for their area of expertise. The community benefits from participation as they learn about science in their everyday lives and see the value of research and STEM (S. Ahmed, DeFino, Connors, Kissack, & Franco, 2014; S. M. Ahmed et al., 2017). Science Café events should emphasize “participation” over “popularization,” to better “demythologize science communication, bringing it out of the cathedra and into everyday life” (Bagnoli & Pacini, 2011). Science Café events are held across the globe and many are now recorded and posted online so that they are broadly accessible to the general public.

The first Science Café was held in 1997 at a wine bar in Leeds, England and was modeled after the the French Cafés Philosophiques, forums held in cafés to discuss philosophical issues (Nielsen, Balling, Hope, & Nakamura, 2015). This format of gathering in a public space to socialize and discuss science has been adopted all over the world in a somewhat grassroots fashion (NOVA Education, 2020). A Science Café is one model of scientific communication with the public that encourages public participation and exploration of emerging issues in medicine, science, technology, the environment, and globalization. The global nature of the Science Café movement is “part of a wider participatory trend” that aims to engage the public with the processes of science (Nielsen et al., 2015, p. 15). However, events are also “adapted to local contexts” to shape and define forms of interactions and dialogue between scientists and their immediate constituencies (Nielsen et al., 2015, p. 3).

Evaluation is a standard component of Science Café events, consisting primarily of participant satisfaction surveys (Einbinder, 2013). Researchers have found that the events are effective at encouraging the discussion of scientific issues among members of the public (Navid & Einsiedel, 2012), including among youth (Hall, Foutz, & Mayhew, 2013; Mayhew & Hall, 2012). The Clinical and Translational Science Institute of SE Wisconsin also evaluated the impact of attendees’ understanding of health and scientific information using a Likert scale assessment of participants’ reported level of confidence across a five-item instrument. They found that attending a Café increased participants’ confidence in health and scientific literacy (S. Ahmed et al., 2014). In addition, Science Cafés are seen as a mechanism to improve the ability of scientists to communicate with the public by providing an opportunity to practice explaining scientific concepts to a general audience (Goldina & Weeks, 2014). This is particularly important for those scientists who may see public engagement as “troublesome or time-consuming” (Mizumachi, Matsuda, Kano, Kawakami, & Kato, 2011). One key challenge of evaluating Science Cafés, or other “dialogue events” aimed at increasing public engagement with science, is understanding the extent to which they increase individual participants’ knowledge about scientific concepts (Lehr et al., 2007). Furthermore, Science Café events may hold greater value as interactions that broadly improve relationships between scientists and society through accessible engagement, rather than serving merely as a mechanism to teach specific ideas, such as in formal scientific lectures or courses (Dijkstra, 2017).

Public Health in Rural Settings

In the US, rural communities disproportionately suffer from a number of adverse health outcomes, including higher rates of obesity and earlier mortality, as well as higher rates of smoking and lower physical activity than their urban counterparts (Garcia et al., 2017; Matthews et al., 2017). Further, recruiting and retaining health care personnel is difficult in rural areas (Asghari et al., 2019; Lafortune & Gustafson, 2019; Thill, Pettersen, & Erickson, 2019) In addition to addressing structural and geographic disparities in rural areas, the social context must also be considered when delivering effective public health interventions in these settings (Gilbert, Laroche, Wallace, Parker, & Curry, 2018). Factors including demographic shifts due to immigration (Nelson & Marston, 2020), poverty (Thurlow, Dorosh, & Davis, 2019), and the necessary engagement of rural residents with extractive industries, such as agriculture or mining (Kulcsar, Selfa, & Bain, 2016), also contribute to health disparities and require interventions that take into account the social and cultural components unique to rural communities.

There has long been an understanding that social networks may be associated with mortality risk (Berkman, 1986) and spread of disease (Bates, Trostle, Cevallos, Hubbard, & Eisenberg, 2007), but they may also provide a framework for behavioral interventions (Eng, 1993; Yun, Kang, Lim, Oh, & Son, 2010). In addition, social transmission of knowledge has been documented in relation to ethnobotanical knowledge (Lozada, Ladio, & Weigandt, 2006; Yates & Ramírez-Sosa, 2004) and agricultural practices and innovations (Flachs, 2017; Stone, 2004). Despite this, evaluations of public health or science-related events do not regularly assess the potential for knowledge dissemination by participants following the event’s occurrence. Our evaluation aimed to understand the potential for knowledge transmiss

Analysis

To evaluate the UE program, we employed a simple pre-post-intervention task. As previously stated, on the first day of the program we asked each student to draw a picture that reflected what they thought about when hearing the term “nature.” We created inventories according to items represented (Sanford, Staples, &. Snowman, 2017; Flowers, Carroll, Green, & Larson, 2015). We repeated this task on the last day of the program before the students were dismissed. Because of unforeseen time constraints (see Limitations, below), we provided students with just five minutes to complete the post-program drawings. We chose to employ this evaluation method after speaking with a school liaison, who expressed concern about the ability of these children to express their opinions in written form. This type of evaluation has been successfully employed with children through eighth grade (Sanford et al., 2017).

Using an emergent thematic coding analysis, researchers analyzed each drawing and developed codes to compare pre-program drawings to post-program drawings in order to determine whether the intervention changed perceptions of what “nature” means to the students. Because of the small sample size (n = 20), each researcher coded all drawings, and the group worked together to reach full agreement. To determine statistical significance, we used a chi-square analysis.

Research Setting

At the University of Iowa, the NIEHS-funded Core Center, the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (EHSRC), and the Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (ICTS) have been organizing Science Cafés since 2013 in various small Iowa towns, most consistently focusing on two communities. Community One, a town of 4,435 residents with a small liberal arts college, and Community Two, a slightly larger town, with 10,420 residents and an alternative business school. Both communities also have a robust agricultural economy that includes produce, livestock, and grain farmers. The Science Café events involve one presenter, usually a researcher or faculty member from the University of Iowa, and the coordinating staff from the EHSRC. The researcher delivers a presentation about 20–30 minutes in length, followed by questions from the audience and discussion. There are no Powerpoint or other slide shows; however, in some cases the presenter may put together a handout that includes two or three slides or graphics with main points from the presentation. Because the events are meant to allow considerable time for discussion and questions from the audience, there are no formal learning objectives or knowledge tests for participants. Most presentations reflect the environmental health focus of the EHSRC. However, the standard evaluation questionnaire distributed after each event solicits suggestions for additional topics from the participants; these topics are then prioritized for future events. Participant suggestions have led to presentations on topics such as wolf habitat in the Midwest, obesity, and healthy sleep habits.

The Science Café location in Community One is a local coffee shop in the center of town, while in Community Two it is the public library. Both of these venues have strong relationships with the EHSRC and support the events by posting flyers for upcoming Cafés. The library in Community Two includes the events on their programming calendar, sends out announcements via Listserv, and sometimes sends press releases to the local paper. The EHSRC regularly advertises in the local paper of Community One. The age of the attendees varies from college students to elder retirees, with retirees being the largest group of consistent participants. There is a core group of about eight participants in each community who attend all of the Cafés, while other attendees vary based on the topic.

This paper presents a novel evaluation of the EHSRC Science Cafés by examining the extent to which participants share what they learned with others. Rather than simply assessing how satisfied or interested participants were in the topic, or assessing individual knowledge, this evaluation seeks to better understand how information travels through communities and social networks, recognizing the importance of social networks as described above, and the implications for broader scientific literacy and environmental health literacy. Given the rural context of the EHSRC Science Cafés, this paper reflects on the implications of knowledge sharing in the rural landscape.

Methods

In the spring of 2019, the EHSRC Community Engagement Core (CEC) staff added several questions to the standard written evaluation that is administered after each Science Café. In addition to asking participants about how far they traveled for the Science Café, how they learned about the event, examples of what they learned during the Café, and to rate their level of satisfaction with the content, participants were asked, “Do you plan to share this information with friends, family, or others? If so, how will you share?” The evaluation also asked if we could follow up with a phone interview in the future. These additional questions were posed at all six Science Café events in spring 2019. The project description was submitted to the University of Iowa’s Institutional Review Board, where it was deemed not to fit the criteria for human subjects’ research. This work was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, P30 ES005605.

A 13-question instrument was designed for use via Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) system. Science Café participants who had indicated their willingness to be interviewed provided their phone numbers on the evaluations and were contacted within two weeks of the Science Café event. The interview reminded participants of their response to the original question, “Do you plan to share this information with friends, family, or others? If so, how will you share?” and asked whether they had in fact shared information from the Science Café and with whom and how they shared it. In addition, participants were asked to describe any other instances when they shared information from any Science Café and who in their communities they felt would most benefit from attending Science Café events.

Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers at the Iowa Social Science Research Center on the campus of the University of Iowa. The CATI system allows for interviews to be transcribed as they are conducted. Following the interviews, written transcriptions were provided to the research team for analysis.

The interview transcripts were coded using both deductive and inductive approaches. The research team read the transcripts and developed an initial set of deductive codes based on the categories of people with whom information was shared: friends/family, social group, professional contacts. A second round of inductive coding generated novel codes from the data and illuminated concepts specific to the population and conditions under which information was shared (e.g. agricultural occupations or cancer survivor) (Legard, Keegan, & Ward, 2003).

Research

Science Café Attendance

In spring 2019, attendance at the Science Cafés ranged from eight to 31 participants (see Table 1). Travel to the events ranged from less than one mile up to 35 miles (one attendee in Community One) with most attendees traveling one mile or less to attend. This suggests the audience for Science Cafés is mostly local residents. In both communities, the highest proportion of attendees report that they are “retired” or “semi-retired”: 38% (n= 12) in Community One and 32% (n= 14) in Community Two. Other occupations identified include farmer, educator, student, medical professional, and self-employed person.

Results from Written Evaluations

Over the course of three Science Cafés in Community One, we received 32 evaluations from a total of 66 participants. In Community Two, we received 44 evaluations from 73 participants. In this paper, we have combined all evaluation results to present the results across both communities.

In response to the question “Do you plan to share this information with friends, family or others?” 56 respondents indicated “yes,” nine indicated “no,” and 11 did not respond to the question. The majority of respondents (33) who said “yes,” indicated that they would do so through conversations with family or friends. Others also indicated social media (two), email (six), and by sharing “notes” (five). Four indicated they would share through a community group or organization (see Figure 1).

In response to the question “Do you plan to share this information with friends, family or others?” 56 respondents indicated “yes,” nine indicated “no,” and 11 did not respond to the question. The majority of respondents (33) who said “yes,” indicated that they would do so through conversations with family or friends. Others also indicated social media (two), email (six), and by sharing “notes” (five). Four indicated they would share through a community group or organization (see Figure 1).

The written evaluation also included a question asking for examples of something the participants learned. Among the responses to this open-ended question were some very specific items, such as “how to count pollen + p2.5-p10 measurements + pollen fragments” following a presentation on air pollution, to more general statements or perceptions of the content. Following a presentation on Iowa agriculture, one participant wrote, “I loved being reminded that conventional ag and diversified small ag are a venn [sic] diagram and have things in common” and another wrote, “intersection of local and global ag in formal and informal ways.” After a presentation on air quality, someone responded: “I learned about air control.”

Results from Interviews

Over the course of the spring 2019 Science Café events, 26 indicated on their evaluation form that they were willing to be interviewed. Of those, we were able to contact and interview 18 individuals, ten women and eight men. Given the relatively narrow focus of the interview guide, this number should be sufficient to reach saturation, the point at which no new themes emerge from the data (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006).

Consistent with the responses in the initial evaluations, most participants shared information in conversations with family or friends:

- I have a friend that I get together with once a week and we chat. We were at lunch and I talked about how Iowa is one of the worst states for cancer. We are also the best research state for cancer, I was kind of bragging on us. (Participant #4)

- I talked about it by word of mouth to a ton of people (Participant #8)

- The bottom line for the lecture after going through many ideas is that the future is solar, and I had a friend who asked me about it and I told him that. (Participant #17)

- I have a friend in Cedar Rapids that I have shared the information with (Participant #15)

Others indicated that they shared information strategically with family or friends who might be particularly interested in it or benefit from it. In some cases, the information was directed at someone who lacked knowledge about the topic: “It was a casual conversation with a friend we were talking about. She’s new to being in a rural area which brought up the different types of agriculture with which she wasn’t familiar with and I was able to share” (Participant #10).

Conversely, information was shared with people who had very specific knowledge of the topic, such as in the case of a cancer survivor or someone remediating mold in a home:

- I shared some points with my mother who is a cancer survivor (Participant #13)

- We were cleaning a house because it was dusty and the new occupants, one of them, has a dust allergy, and I said I was just at the Science Café on air quality and the question was “What is one thing we can do ourselves on air quality?” and the teacher said basement mold and the person I was talking to said the moldy basement was a bigger issue than the dust and I was able to confirm what they said with the advice of an expert. (Participant #26)

Others noted that the topic was relevant to their professional life and so they discussed it with colleagues in a professional capacity. In this context, student status is considered a professional setting:

- I brought it up in class and told them what it was about. (Participant #8)

- Since I’m a farmer I’ll sometimes relate something that came out of there to someone else in the same profession. (Participant #11)

- Friends who are water quality testers like me, we all agreed that we need to be referencing data and all of us generally agreed that this ups the game of water quality of Iowa and is the proof that we need to show that we have to turn things around. (Participant #16)

- Finally, a couple of respondents referenced formal social or community groups that they shared information with:

- [with] the breakfast club…I told it to my husband, my friends at the book club, and several other people. (Participant #5)

- I work with the local Sierra Club so it was an interesting background to have. (Participant #21)

In some cases, respondents referenced their own reputations or positions within the community, indicating that the Science Café information provided additional weight or legitimacy to areas of concern that they have been known to discuss:

- Informally as always. They’re used to me talking about local ag at this point. (Participant #14)

- It was about agriculture and I am a farmer so it is my life. (Participant #9)

- I talk about it in my community and how we can implement it in our community. I also talk about compost and trash a lot so I might be a little excited about it. (Participant #14)

Most respondents indicated that they shared information verbally or through casual conversations. A few, however, noted that they shared information via written notes, video, or online mechanisms:

- I take notes and I give the whole thing to my husband and my friends. (Participant #5)

- Well that is odd that you called because just an hour ago I was talking to someone about it. The fellow had a graphic on the information. It turns out the 5,000 pigs put out the sewage amount of 20,000 people. I’m going to take the map that he showed and make it a poster size and put it around town so that people see it because they need to. (Participant #20)

- A friend put a video that I made up on a forum. I didn’t spread it but she did. (Participant #20)

Discussion

These results shed light on the diversity of social settings and groups that individuals in small rural communities may encounter and engage with. One challenge of conducting community outreach or participatory research in rural communities is that low populations make it difficult to generate impactful numbers of participants or attendees at events. However, responses indicated a wide number of settings, both formal and informal, in which information was shared. These included book clubs, breakfast clubs, the local Sierra Club chapter, and with family members, fellow students, and colleagues. In some cases, participants sought out individuals who they knew would be interested in the information (e.g., a parent who is a cancer survivor). In other cases, interview respondents indicated that they were asked about the event, or the topic came up, and they had information to share.

Notably, the content gleaned from Science Café events provided legitimacy and evidence for several participants in their interactions, particularly in formal settings such as the workplace or a community organization. For example, content from a water quality event generated a longer discussion among community water testers about the importance of good data and evidence in water quality discussions. In other contexts, such as cancer-related research, the Science Café material provided information about resources in Iowa, allowing the participant to “brag” about research productivity in the state. Knowledge sharing among social networks can be an important conduit for information transmission, particularly in rural areas (Burch, 2007; Mtega et al., 2013). Even relatively small events like these Science Cafés can enhance knowledge in formal settings, broadening the initial reach of the event and informing professional networks as well as informal social groups.

In addition, several participants indicated that they are known for being interested in a topic, as evidenced by comments such as “I talk about composting and trash a lot” and “They’re used to me talking about local ag” as well as “I am a farmer, so it’s my life.” The literature related to program development in sustainable food systems suggests that many new endeavors are initiated by “champions” who engage with the community and promote their cause (Bagdonis, Hinrichs, & Schafft, 2008). Likewise, other evaluation strategies have examined the qualities of people who support initiatives in quality improvement (Demes et al., 2020). Recognizing that these highly engaged “champions” may participate in other events, gleaning information and resources to pass along in other settings, is a potentially new way to think about how content from a Science Café event might reach additional community members. Future evaluations in these communities could include social network analysis or mapping to better understand the social and professional channels through which information may be distributed (Wasserman & Faust, 1994).

While most participants shared information verbally by reporting that they described the content of the Science Café to others, some developed additional materials or used other media. One participant stated that they took written notes, which they shared, and another described developing posters and videos for distribution. This was an unexpected product and suggests there may be additional opportunities to engage with Science Café participants to co-develop products or materials related to the events’ content. Providing content in a way that participants can reproduce and share, such as an electronic version of the standard handout or graphics, could further encourage participants to develop follow-up materials after the event.

In this small study, respondents’ diverse reports of what they learned, in conjunction with the wide array of approaches to sharing information, suggest that Science Cafés may serve as more than simply sites where the public learns about scientific concepts. Among participants in this study, some were inspired or reminded about the intersections between systems (such as conventional and alternative agriculture), some became excited about, and advocates for, cutting-edge cancer research in their communities, or they used the content to champion projects in local organizations. When viewed from this perspective, Science Cafés have a great deal of potential to improve the relationships between scientists and society. This study contributes a new approach for evaluating Science Café events. Future research could link pre-determined learning objectives with an evaluation of how those objectives are communicated more broadly.

Conclusion

This study suggests that evaluating small events in rural communities can benefit from learning not only who attends and their levels of satisfaction, but also how they may recount and communicate the information they learn with their social and professional networks. Recognizing that participants may be leaders in local groups, champions for causes, or may glean information that is particularly relevant for a friend or family member can help organizers develop programming that can be tailored to and/or shared in a variety of media. In addition, being attentive to those who are motivated to develop additional outputs, such as posters or video, can help organizers expand the reach of what is otherwise a relatively small event. Understanding how science may be communicated via social networks can assist in developing programs with the potential to have a broad community impact, beyond the setting of one individual event.

About the Authors

Jacqueline Curnick is the Program Coordinator of the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center Community Engagement Core at the University of Iowa. She holds a Master of Sustainable Development Practice with a focus in environmental communication.

Jacqueline Curnick is the Program Coordinator of the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center Community Engagement Core at the University of Iowa. She holds a Master of Sustainable Development Practice with a focus in environmental communication.

Brandi Janssen is a Clinical Associate Professor of Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of Iowa. She directs Iowa’s center for Agricultural Safety and Health (I-CASH) and the Community Engagement Core for the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (EHSRC).

Brandi Janssen is a Clinical Associate Professor of Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of Iowa. She directs Iowa’s center for Agricultural Safety and Health (I-CASH) and the Community Engagement Core for the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (EHSRC).

References

Ahmed, S., DeFino, M. C., Connors, E. R., Kissack, A., & Franco, Z. (2014). Science cafés: Engaging scientists and community through health and science dialogue. Clinical and Translational Science, 7(3), 196–200. doi:10.1111/cts.12153

Ahmed, S. M., DeFino, M., Connors, E., Visotcky, A., Kissack, A., & Franco, Z. (2017). Science cafés: Transforming citizens to scientific citizens—What influences participants’ perceived change in health and scientific literacy? Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 1(2), 129–134. doi:10.1017/cts.2016.24

Asghari, S., Kirkland, M. C., Blackmore, J., Boyd, S. E., Farrell, A., Rourke, J., . . . Walczak, A. (2019). A systematic review of reviews: Recruitment and retention of rural family physicians. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 25(1), 20–30.

Bagdonis, J. M., Hinrichs, C. C., & Schafft, K. A. (2008). The emergence and framing of farm-to-school initiatives: Civic engagement, health and local agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values, 26(1–2), 107–119. doi:10.1007/s10460-008-9173-6

Bagnoli, F., & Pacini, G. (2011). Sipping science in a café. Procedia Computer Science, 7, 194–196.

Bates, S. J., Trostle, J., Cevallos, W. T., Hubbard, A., & Eisenberg, J. N. (2007). Relating diarrheal disease to social networks and the geographic configuration of communities in rural Ecuador. American Journal of Epidemiology, 166(9), 1088–1095.

Berkman, L. F. (1986). Social networks, support, and health: Taking the next step forward. American Journal of Epidemiology, 123(4), 559–562.

Burch, S. (2007). Knowledge sharing for rural development: Challenges, experiences and methods. Quito: Agencia Latinoamericana de Información (Latin American Information Agency). Retrieved from https://www.alainet.org/sites/default/files/tss%20ingles.pdf

Demes, J. A. E., Nickerson, N., Farand, L., Montekio, V. B., Torres, P., Dube, J. G., . . . Jasmin, E. R. (2020). What are the characteristics of the champion that influence the implementation of quality improvement programs? Evaluation and Program Planning, 80, 101795. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2020.101795

Dijkstra, A. (2017). Analysing Dutch science cafés to better understand the science-society relationship. Journal of Science Communication, 16(1), A03.

Einbinder, A. (2013). Understanding the popular Science Café experience using the excellent judges framework. ILR, 6.

Eng, E. (1993). The Save our Sisters Project. A social network strategy for reaching rural black women. Cancer, 72(S3), 1071-1077.

Flachs, A. (2017). “Show Farmers”: Transformation and performance in Telangana, India. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment, 39(1), 2–34. doi:10.1111/cuag.12085

Garcia, M., Faul, M., Massetti, G., Thomas, C. C., Hong, Y., Bauer, U. E., & Iademarco, M. F. (2017). Reducing potentially excess deaths from the five leading causes of death in the rural United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(2), 1–7.

Gilbert, P. A., Laroche, H. H., Wallace, R. B., Parker, E. A., & Curry, S. J. (2018). Extending work on rural health disparities: A commentary on Matthews and colleagues’ report. The Journal of Rural Health, 34(2), 119–121. doi:10.1111/jrh.12241

Goldina, A., & Weeks, O. I. (2014). Science Café course: An innovative means of improving communication skills of undergraduate biology majors. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 15(1), 13–17.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822×05279903

Hall, M. K., Foutz, S., & Mayhew, M. A. (2013). Design and impacts of a youth-directed Café Scientifique program. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 3(2), 175–198. doi:10.1080/21548455.2012.715780

Kulcsar, L. J., Selfa, T., & Bain, C. M. (2016). Privileged access and rural vulnerabilities: Examining social and environmental exploitation in bioenergy development in the American Midwest. Journal of Rural Studies, 47, 291–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.01.008

Lafortune, C., & Gustafson, J. (2019). Interventions to improve recruitment and retention of physicians in rural and remote Canada: A systematic review. University of Western Ontario Medical Journal 88(1).

Legard, R., Keegan, J., & Ward, K. (2003). In-depth interviews. In J. Richie & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp. 139–168). London: Sage Publishing.

Lehr, J. L., McCallie, E., Davies, S. R., Caron, B. R., Gammon, B., & Duensing, S. (2007). The value of “dialogue events” as sites of learning: An exploration of research and evaluation frameworks. International Journal of Science Education, 29(12), 1467–1487.

Lozada, M., Ladio, A., & Weigandt, M. (2006). Cultural transmission of ethnobotanical knowledge in a rural community of northwestern Patagonia, Argentina. Economic Botany, 60(4), 374–385.

Matthews, K. A., Croft, J. B., Liu, Y., Lu, H., Kanny, D., Wheaton, A. G., . . . Holt, J. B. (2017). Health-related behaviors by urban-rural county classification—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 66(5), 1.

Mayhew, M. A., & Hall, M. K. (2012). Science communication in a Café Scientifique for high school teens. Science Communication, 34(4), 546–554. doi:10.1177/1075547012444790

Mizumachi, E., Matsuda, K., Kano, K., Kawakami, M., & Kato, K. (2011). Scientists’ attitudes toward a dialogue with the public: A study using “science cafes.” Journal of Science Communication, 10(4), A02.

Mtega, W. P., Dulle, F., Benard, R., Mtega, W., Dulle, F., & Benard, R. (2013). Understanding the knowledge sharing process among rural communities in Tanzania: A review of selected studies. Knowledge Management and E-Learning: An International Journal, 5(2), 205–217.

Navid, E. L., & Einsiedel, E. F. (2012). Synthetic biology in the Science Café: What have we learned about public engagement? Journal of Science Communication, 11(4), A02.

Nelson, K. A., & Marston, C. (2020). Refugee migration histories in a meatpacking town: Blurring the line between primary and secondary migration. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 21(1), 77–91.

Nielsen, K. H., Balling, G., Hope, T., & Nakamura, M. (2015). Sipping science: The interpretative flexibility of science cafés in Denmark and Japan. East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal, 9(1), 1–21.

NOVA Education. (2020). Science Cafés 101. Retrieved from www.sciencecafes.org

Stone, G. D. (2004). Biotechnology and the political ecology of information in India. Human Organization, 63(2), 127–140.

Thill, N., Pettersen, L., & Erickson, A. (2019). A reality tour in rural and public health nursing. Online Journal of Rural Nursing & Health Care, 19(1).

Thurlow, J., Dorosh, P., & Davis, B. (2019). Demographic change, agriculture, and rural poverty. In C. Campanhola & S. Pandey (Eds.), Sustainable food and agriculture: An integrated approach (pp. 31–53). London: Academic Press.

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. In M. Granovetter (Gen. Ed.), Structural analysis in the social sciences: Vol. 8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yates, S., & Ramírez-Sosa, C. R. (2004). Ethnobotanical knowledge of Brosimum alicastrum (Moraceae) among urban and rural El Salvadorian adolescents. Economic Botany, 58(1), 72–77.

Yun, E. H., Kang, Y. H., Lim, M. K., Oh, J.-K., & Son, J. M. (2010). The role of social support and social networks in smoking behavior among middle and older aged people in rural areas of South Korea: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 78.

Appendix A

Science Café Evaluation Questions

1. Name

2. Profession

3. Email

4. Are you already on the mailing list?

5. Are you willing to be contacted via phone for a brief interview? If so, please list phone number.

6. How did you learn about the event?

- Email from school/professor

- Flyer

- Newspaper

- Email list from EHSRC

- Other (please describe)

7. Please rate the following as excellent, good, fair, or poor:

- Presentation

- Group discussion

8. Examples of something you learned:

9. Do you plan to share this information with friends, family, or others? If so, how will you share?

10. Are there any topics you would like to learn about in a future Science Café?

11. Do you have any suggestions for how we can improve the Science Café?

Appendix B

Phone Interview Questions

Hello, may I speak with (first name, last name)? This is __ calling from the University of Iowa, and you are being contacted because you had previously indicated at a recent Science Café event that you were willing to be interviewed.

On the evaluation form at the most recent Science Café you attended, we asked you: Do you plan to share this information with friends, family, or others? If so, how will you share?

You responded: SOME FORM OF YES

1. Why did you indicate you would share information? For example, it was interesting, relevant, important, you had someone in mind, etc.

2. Did you discuss the information you learned at the Science Café in person, by email, or by telephone with anyone? Answer options: Yes, No, I don’t know/remember, Refused (If no, go to question 6)

3. How many people?

4. Can you describe that interaction or discussion?

5. What was the outcome of the interaction? For example, did the person indicate interest, say they learned something new, disagree or take issue with the information?

6. (If answered no to question 2) Why have you not talked about the Science Café with anyone? For example, you didn’t think of it, it wasn’t important information, you are not comfortable sharing, etc.

7. (If answered no to question 2) Do you think you’ll talk about it in the future?

FOR ALL: Now I’d like to ask you about the Science Cafés in general.

8. About how many Science Café events have you attended?

9. Have you ever talked about past Science Café content with friends, coworkers, or family members following the event? Answer options: Yes, No, I don’t know/remember, Refused (If no, go to question 12)

10. Can you tell me about or describe a conversation you’ve had with friends, coworkers, or family members about a Science Café?

11. Do you think the information you shared was new to the person or people you spoke with?

12. (If answered no to question 9) Why have you not talked about the Science Café with anyone? For example, you didn’t think of it, it wasn’t important information, you are not comfortable sharing, etc.

13. Who in your community would most benefit from the information shared during Science Café events?

On the evaluation form at the most recent Science Café you attended, we asked you: Do you plan to share this information with friends, family, or others? If so, how will you share?

You responded: SOME FORM OF NO

1. Why did you indicate you would not share the information? For example, not interesting, relevant, important, no one to share with, etc.

2. Did you discuss the information you learned at the Science Café with anyone? Answer options: Yes, No, I don’t know/remember, Refused (If no, go to question 8)

3. How many people?

4. Can you describe that interaction/discussion?

5. Did you communicate about the Science Café by email or telephone with anyone?

6. Can you describe that interaction?

7. What was the outcome of the interaction? Did the person indicate interest, say they learned something new, disagree or take issue with the information? (Go to question 9)

8. (If answered no to question 2) Why have you not talked about the Science Café? For example, didn’t think of it, wasn’t important information, not comfortable sharing.

9. Do you think you’ll talk about it in the future?

FOR ALL: Now I’d like to ask you about the Science Cafés in general.

10. About how many Science Café events have you attended?

11. Have you ever talked about past Science Café content with friends, coworkers, or family members following the event? (If no, go to question 14)

12. Can you tell me about or describe a conversation you’ve had with friends, coworkers, or family members about a Science Café?

13. Do you think the information you shared was new to the person or people you spoke with? (Go to question 15)

14. (If answered no to question 11) Why have you not talked about the Science Café? For example, didn’t think of it, wasn’t important information, not comfortable sharing.

15. Who in your community would most benefit from the information shared during Science Café events?

For those who responded: UNSURE OR BLANK

Intro language—they are being called because they indicated at a recent Science Café event that they were willing to be interviewed.

You recently attended a Science Café presentation,

1. Did you discuss the information you learned at the science cafe with anyone? (If no, go to question 7)

2. How many people?

3. Can you describe that interaction/discussion?

4. Did you communicate about the Science Café by email or telephone with anyone?

5. Can you describe that interaction?

6. What was the outcome of the interaction? Did the person indicate interest, say they learned something new, disagree or take issue with the information? (Go to question 8)

7. (If answered no to question 1) Why have you not talked about the Science Café? For example, didn’t think of it, wasn’t important information, not comfortable sharing.

8. Do you think you’ll talk about it in the future?

FOR ALL: Now I’d like to ask you about the Science Cafés in general.

9. About how many Science Café events have you attended?

10. Have you ever talked about past Science Café content with friends, coworkers, or family members following the event? (If no, go to question 13)

11. Can you tell me about/describe a conversation you’ve had with friends, coworkers, or family members about a Science Café?

12. Do you think the information you shared was new to the person or people you spoke with? (Go to question 14)

13. (If answered no to question 10) Why have you not talked about the Science Café? For example, didn’t think of it, wasn’t important information, not comfortable sharing.

14. Who in your community would most benefit from the information shared during Science Café events?

Download the article

Download (PDF, 3.81MB)

In response to the question “Do you plan to share this information with friends, family or others?” 56 respondents indicated “yes,” nine indicated “no,” and 11 did not respond to the question.

In response to the question “Do you plan to share this information with friends, family or others?” 56 respondents indicated “yes,” nine indicated “no,” and 11 did not respond to the question. Jacqueline Curnick is the Program Coordinator of the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center Community Engagement Core at the University of Iowa. She holds a Master of Sustainable Development Practice with a focus in environmental communication.

Jacqueline Curnick is the Program Coordinator of the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center Community Engagement Core at the University of Iowa. She holds a Master of Sustainable Development Practice with a focus in environmental communication. Brandi Janssen is a Clinical Associate Professor of Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of Iowa. She directs Iowa’s center for Agricultural Safety and Health (I-CASH) and the Community Engagement Core for the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (EHSRC).

Brandi Janssen is a Clinical Associate Professor of Occupational and Environmental Health at the University of Iowa. She directs Iowa’s center for Agricultural Safety and Health (I-CASH) and the Community Engagement Core for the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (EHSRC).

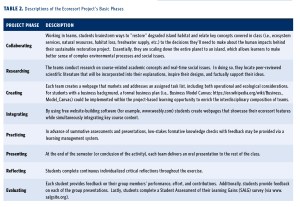

This activity is applicable to a wide range of disciplines and academic levels (Table 3), and instructors can incorporate the activity in multiple ways. For example, they might

This activity is applicable to a wide range of disciplines and academic levels (Table 3), and instructors can incorporate the activity in multiple ways. For example, they might

David Green specializes in advancing learner-centered curricula in health sciences, medical education, and STEM education.

David Green specializes in advancing learner-centered curricula in health sciences, medical education, and STEM education.

Steven Bachofer teaches chemistry and environmental science at Saint Mary’s College and has worked with the Alameda Point Collaborative for more than 15 years through his affiliation with the SENCER project. He has also co-authored a SENCER model course with Phylis Martinelli, addressing the redevelopment of a Superfund site (NAS Alameda).

Steven Bachofer teaches chemistry and environmental science at Saint Mary’s College and has worked with the Alameda Point Collaborative for more than 15 years through his affiliation with the SENCER project. He has also co-authored a SENCER model course with Phylis Martinelli, addressing the redevelopment of a Superfund site (NAS Alameda).  Marque Cass has been in the field of education since before his graduation from UC-Davis, where he earned a BS in Community and Regional Development with an emphasis in Organization and Management. Since January 2019, he has been the youth program coordinator for Alameda Point Collaborative, doing mentoring and advocacy work for formerly homeless families. More recently, he has been elected a community partner liaison with Saint Mary’s College, working to help create stronger networks between organizations.

Marque Cass has been in the field of education since before his graduation from UC-Davis, where he earned a BS in Community and Regional Development with an emphasis in Organization and Management. Since January 2019, he has been the youth program coordinator for Alameda Point Collaborative, doing mentoring and advocacy work for formerly homeless families. More recently, he has been elected a community partner liaison with Saint Mary’s College, working to help create stronger networks between organizations. Laura B. Liu, Ed.D. is an assistant professor and Coordinator of the English as a New Language (ENL) Program in the Division of Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus (IUPUC). Her research and teaching include the integration of civic science and funds of knowledge into elementary and teacher education curricula and instruction.

Laura B. Liu, Ed.D. is an assistant professor and Coordinator of the English as a New Language (ENL) Program in the Division of Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus (IUPUC). Her research and teaching include the integration of civic science and funds of knowledge into elementary and teacher education curricula and instruction. Taylor Russell is an elementary teacher and earned her Bachelor of Science in Elementary Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus (IUPUC), with a dual license in teaching English as a New Language (ENL).

Taylor Russell is an elementary teacher and earned her Bachelor of Science in Elementary Education at Indiana University-Purdue University Columbus (IUPUC), with a dual license in teaching English as a New Language (ENL).

Diana Samaroo is a professor in the Chemistry Department at NYC College of Technology in Brooklyn, New York.

Diana Samaroo is a professor in the Chemistry Department at NYC College of Technology in Brooklyn, New York.  Liana Tsenova is a professor emerita in the Biological Sciences Department at the New York City College of Technology. She earned her MD degree with a specialty in microbiology and immunology from the Medical Academy in Sofia, Bulgaria. She received her postdoctoral training at Rockefeller University, New York, NY. Her research is focused on the immune response and host-directed therapies in tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. Dr. Tsenova has co-authored more than 60 publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals and books. At City Tech she has served as the PI of the Bridges to the Baccalaureate Program, funded by NIH. She was a SENCER leadership fellow. Applying the SENCER ideas, she mentors undergraduates in interdisciplinary projects, combining microbiology and infectious diseases with chemistry and mathematics, to address unresolved epidemiologic, ecologic, and healthcare problems.

Liana Tsenova is a professor emerita in the Biological Sciences Department at the New York City College of Technology. She earned her MD degree with a specialty in microbiology and immunology from the Medical Academy in Sofia, Bulgaria. She received her postdoctoral training at Rockefeller University, New York, NY. Her research is focused on the immune response and host-directed therapies in tuberculosis and other infectious diseases. Dr. Tsenova has co-authored more than 60 publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals and books. At City Tech she has served as the PI of the Bridges to the Baccalaureate Program, funded by NIH. She was a SENCER leadership fellow. Applying the SENCER ideas, she mentors undergraduates in interdisciplinary projects, combining microbiology and infectious diseases with chemistry and mathematics, to address unresolved epidemiologic, ecologic, and healthcare problems. Sandie Han is a professor of mathematics at New York City College of Technology. She has extensive experience in program design and administration, including service as the mathematics department chair for six years, PI on the U.S. Department of Education MSEIP grant, and co-PI on the NSF S-STEM grant. Her research area is number theory and mathematics education.

Sandie Han is a professor of mathematics at New York City College of Technology. She has extensive experience in program design and administration, including service as the mathematics department chair for six years, PI on the U.S. Department of Education MSEIP grant, and co-PI on the NSF S-STEM grant. Her research area is number theory and mathematics education. Urmi Ghosh-Dastidar is the coordinator of the Computer Science Program and a professor in the Mathematics Department at New York City College of Technology – City University of New York. She received a PhD in applied mathematics jointly from the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University and a BS in applied mathematics from The Ohio State University. Her current interests include parameter estimation via optimization, infectious disease modeling, applications of graph theory in biology and chemistry, and developing and applying bio-math related undergraduate modules in various SENCER related projects. She has several publications in peer-reviewed journals and is the recipient of several MAA NREUP grants, a SENCER leadership fellowship, a Department of Homeland Security grant, and several NSF and PSC-CUNY grants/awards. She also has extensive experience in mentoring undergraduate students in various research projects.

Urmi Ghosh-Dastidar is the coordinator of the Computer Science Program and a professor in the Mathematics Department at New York City College of Technology – City University of New York. She received a PhD in applied mathematics jointly from the New Jersey Institute of Technology and Rutgers University and a BS in applied mathematics from The Ohio State University. Her current interests include parameter estimation via optimization, infectious disease modeling, applications of graph theory in biology and chemistry, and developing and applying bio-math related undergraduate modules in various SENCER related projects. She has several publications in peer-reviewed journals and is the recipient of several MAA NREUP grants, a SENCER leadership fellowship, a Department of Homeland Security grant, and several NSF and PSC-CUNY grants/awards. She also has extensive experience in mentoring undergraduate students in various research projects.

Matthew A. Fisher is a professor of chemistry at Saint Vincent College, where he has taught since 1995. He teaches undergraduate biochemistry, general chemistry, and organic chemistry lecture. Active in the American Chemical Society, he has been involved in ACS’ public policy work for more than 15 years and was recognized as an ACS Fellow in 2015. His research interests are in the scholarship of teaching and learning, particularly related to integrative learning in the context of undergraduate chemistry.

Matthew A. Fisher is a professor of chemistry at Saint Vincent College, where he has taught since 1995. He teaches undergraduate biochemistry, general chemistry, and organic chemistry lecture. Active in the American Chemical Society, he has been involved in ACS’ public policy work for more than 15 years and was recognized as an ACS Fellow in 2015. His research interests are in the scholarship of teaching and learning, particularly related to integrative learning in the context of undergraduate chemistry.

Jackson Z. Miner is a graduate of Ball State University with a major in secondary life science education, a major in biology with a concentration in zoology, and a minor in women and gender studies. He is starting his career as a secondary science educator and has a passion for diversity, inclusion, and equity. Contact at jzminer@bsu.edu.

Jackson Z. Miner is a graduate of Ball State University with a major in secondary life science education, a major in biology with a concentration in zoology, and a minor in women and gender studies. He is starting his career as a secondary science educator and has a passion for diversity, inclusion, and equity. Contact at jzminer@bsu.edu. Dr. Rona Robinson-Hill is an assistant professor at Ball State University in Muncie, IN. Her research focuses on teaching and learning in elementary and secondary science methods courses, so that pre-service teachers learn how to reach underserved populations by using culturally relevant, inquiry-based pedagogy. She is the Principal Investigator of the Training Future Scientist (TFS) Program, which exposes elementary and second pre-service teachers to authentic pedagogy to reduce their fears about teaching science to diverse underserved students. This program provides instruction in inquiry-based elementary science teaching for diverse underserved students in grades K–5 and gives secondary science educators an opportunity to perform research in a STEM research lab. Contact at rmrobinsonhi@bsu.edu.

Dr. Rona Robinson-Hill is an assistant professor at Ball State University in Muncie, IN. Her research focuses on teaching and learning in elementary and secondary science methods courses, so that pre-service teachers learn how to reach underserved populations by using culturally relevant, inquiry-based pedagogy. She is the Principal Investigator of the Training Future Scientist (TFS) Program, which exposes elementary and second pre-service teachers to authentic pedagogy to reduce their fears about teaching science to diverse underserved students. This program provides instruction in inquiry-based elementary science teaching for diverse underserved students in grades K–5 and gives secondary science educators an opportunity to perform research in a STEM research lab. Contact at rmrobinsonhi@bsu.edu.